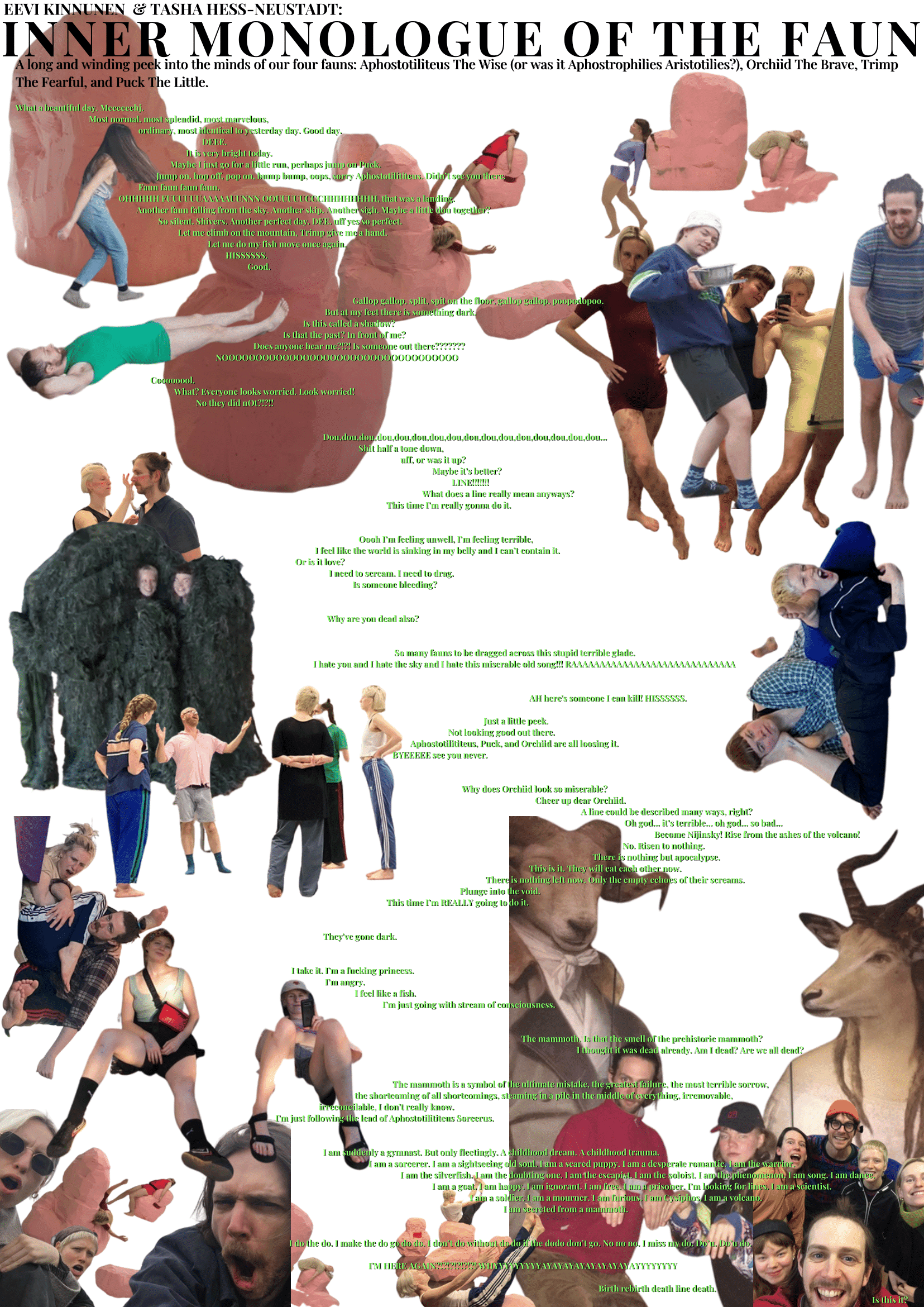

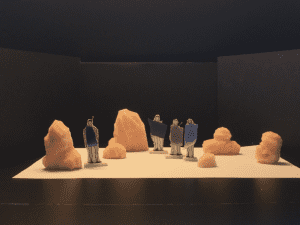

In the short story Simone Mousset composed to express narrative nested within The Empire of the Faun Imaginary, we are introduced to a magical reality on a far off planet on which four alien Fauns live in a white glade. They regulate their breathing as the air pressure shifts through the course of this strange world’s day by singing in apparently ‘harmonious’ unison. The story not only offers hints of the conceptual infrastructure that undergirds this piece, but it also articulates a problem that haunts our every attempt to make sense of our own reality as it unfolds with complete ambivalence to our very existence. The problem becomes apparent when, eventually, the ‘harmonious’ existence of the Fauns is ruptured when one faun sings out of unison. This doesn’t cause a problem for their breathing. The singing alone is sufficient to regulate it, which reveals something unsettling about their, now lost, unity. They persist in attempting to reclaim their ‘harmony’, becoming increasingly frustrated as they fail to achieve again something that had previously not even been possible to think of in terms of achievement. The ‘harmony’ had just been what it was to exist. And the quasi-immortality of the fauns meant that they have experienced the non-conscious ease of producing their collective song for millennia. This rupture, then, is so confounding for them because it is like a tear in the fabric of their reality. But it is this tear that makes reality apprehensible to them as something at all.

The tear, then, provides the vantage point from which what they are doing can be understood as singing. When bees dance, they are communicating the location of pollen. When birds sing, they are looking for or calling to a mate. These things are practical activities for the reproduction of life. It is us, humans, outsiders to these creatures concerns, that add these aesthetic meanings to these activities as we do to our own. This isn’t to trivialize aestheticization, rather it is to point to the complex work it does to link material reality to our ideas about it. The loss of ‘unity’ sets the fauns on a journey to perform the same act of abstraction on what had been their immediate, unmediated state of being. The aesthetic judgment, following the rupture, transforms their vocalization into a song.

Something happens to the Fauns, then, when they realise the fallibility of the life sustaining processes they had taken for granted. They still sustain life, but the subtle failure has left the process reified. The ‘harmony’ that had been their reality becomes something they prefer to the discord they are currently stricken with. And with this feeling of preference, their reality is split between what apparently is, and a mental representation of what once was and what could be again. But the very act of producing this preference, of representing their world to themselves, means it will never be realised again. And, by representing their world to themselves, they start to cast doubts as to whether it was ever actually like they now imagine it was before. Even if it was, it can never be again because, definitionally, representation can never be identical to what it represents.

This irresolvable disjunction permeates the conversations and correspondences between Mousset and myself as we talk about this project. The Empire of the Faun Imaginary, then, is a piece that exists in the melancholy of what Mousset has described as her motivation, what she calls a “painful pull towards irrevocable transformation”. This is what happens to the Fauns. The disruption to their patterning of existence has introduced them to their own preferences, which becomes the very moment at which it is no longer possible to meet them. They have been transformed into creatures like us, creatures that represent the world to themselves in ways that cannot match experience. In a perhaps overly grand sense, this is a problematic that permeates the Western art tradition, and is the source of unending angst for artists concerned about living up to an ideal of art making and who are continually faced, instead, with whatever particularity they produced in actuality. But really it is more common place than that. It is the party one hosts that cannot live up to your expectations, the education one takes that didn’t provide you the answers you sought, the job that barely even fulfils the ideal of making a living, and the partner who, in the end, you didn’t like as much as you hoped you would.

The issue here though is not reality. It is instead our relation to it. For the Fauns, it is their inability to accept that they are unable to live what they idealise. The pain Mousset speaks of is caused not merely by representing the world through unreasonable expectations, but by occupying a meta position of representations which supposes our representations of reality should have some bearing on it. The pain of believing that what you experience as a will for the world to be or become a certain way is capable of shaping the world towards its desires, when nothing could be further from the truth. When that will for what could be encounters what is, it will have to negotiate with it on those terms. The party, the education, the job, the partner can only do what they can do, and your representations of them often fails to take that into account.

The routes through this are fraught and traumatic. This is what we see the Fauns go through, the trauma of an irrevocable transformation. In her own words, Mousset describes how what she expresses in this piece, “is a delirious and fantasising yearning for this all too familiar tussle with loss and meaninglessness to be transformed or be transcended by an unimaginable, catastrophic and perhaps even cathartic change of the very essence of all things, towards an unknown, but other state.” So, what we see with the Fauns is a close up, concrete examination of an abstract problem. The piece then is an unfolding of what Donna Haraway might call “staying with the trouble”. And while it is abstract, the trouble here is one with a great deal of contemporary relevance.

For people of mine and Mousset’s generation, the class were a part of, in the part of the planet we’re from, we grew up, much like the Fauns, in an apparently stable world. A world in which we were told the future would either be like the past or an improvement on it. But in the last fifteen years we have come to learn that this is not necessarily the case, and for most people, it never was. Whatever systems had allowed the life of the Fauns to seem stable to them worked by slowly falling apart. And then those systems fell apart entirely. This is a very similar moment for us and those still fortunate enough to work in the arts or who get to see performances such as this one. The world built after the horrors of the 20th century – after European extractive violence had turned on itself, and commitments were made to not let it happen again by intensifying market interdependency and individualizing experience – has slowly been coming apart from within for decades. In this winter of crisis at the beginning of what will be a decade of crises, our pseudo stable world may well fall further apart still.

From our conversations, The Empire of the Faun Imaginary is an opportunity to objectify the traumatic process of transformations. Through the Fauns, we can perhaps objectify the violence we inflict on ourselves and others when we insist on committing to representations that no longer, in any way, match the world. The irrevocable transformation then offers an open, ambivalent question. Will we go out screaming about that which has been already lost forever, just to hold on to who we believed we were? Or will we let ourselves become something else with and through the new world that is emerging?

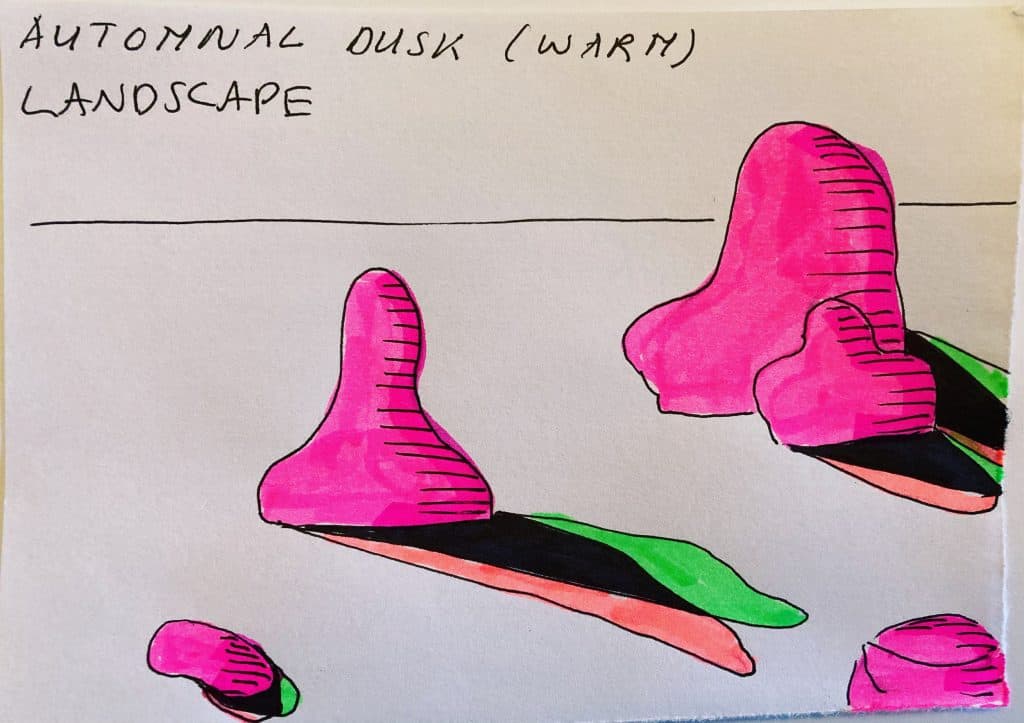

‘Colour Research Hair and Faun’ – Lydia Sonderegger – Stage & Costume Designer

‘Colour Research Hair and Faun’ – Lydia Sonderegger – Stage & Costume Designer